Satyagraha: Soul Force

God only Acts & Is, in existing beings or Men."

— William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1793.Truth Force

Mahatma Gandhi called it Satyagraha, Truth Force.

Martin Luther King called it Soul Force.

It is mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita, as Karma Yoga, Action Yoga, consecrated action.

Or we could call it Engaged Spirituality.

It is the means by which a person with spiritual beliefs may become involved in the political world.

You’ve probably seen the films from the days of the British Raj. An Indian peasant walks up to a line of British Soldiers, who refuse to let him pass. He attempts to pass anyway. One of the soldiers knocks him down with the butt of his gun. The peasant stands up and again attempts to pass. The soldier knocks him down again. More peasants walk to the line. More and more of them are knocked down. All of them continue to get up and walk back, standing up to the power and the might of the British Empire, putting their fragile bodies on the line, suffering for a political cause.

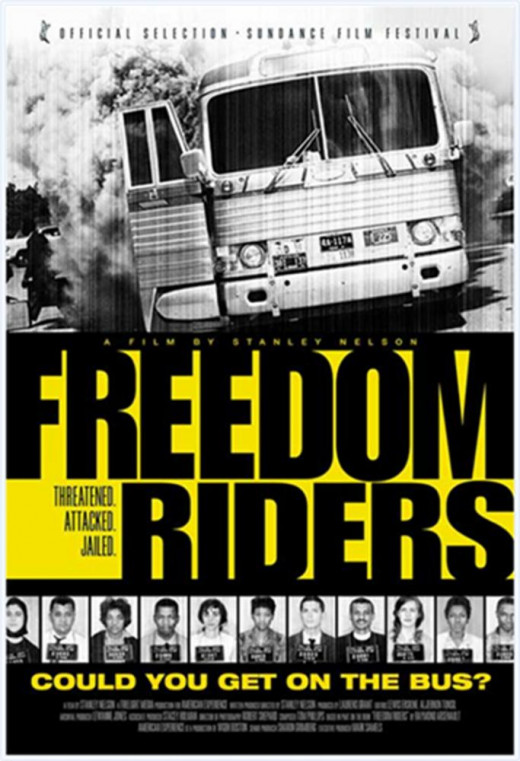

Freedom Riders

You will also have heard of the Freedom Riders, the mixed race groups who rode on Interstate buses into the segregated South in the crucial years of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, challenging local laws permitting racial segregation on buses, and in parks and restaurants. Often they were beaten up for their troubles, or thrown into Jail.

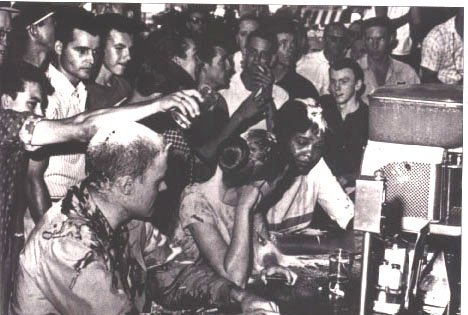

You will have seen the marches, in Montgomery and Birmingham in the state of Alabama: the civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, linking arms as they approach the state troopers. You may have seen the images of the Greenboro sit-ins of the early 60s, when black people sat at segregated food-counters in Woolworths and other stores demanding to be served. Can you imagine the intensity of that? Not only were they breaking the law, they were defying the accepted behaviour of their day and facing the hatred of the crowd. Anyone who has ever been in a similar position, feeling waves of hatred bearing down upon them, will know what courage that took, what spirit, what inner strength.

This is Satyagraha in action.

The Voice of Honest Indignation

More recently, in the UK, you will have seen the peace camps at Greenham Common and Molesworth. You will have seen Druids and other road protesters building tree houses and fortifications along the route of the bypass at Newbury. You will have heard Brian Haw giving his alternative Christmas speech from his camp in Parliament Square, or have seen interviews with members of the Occupy Movement from the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London.

What all of these movements share is a common tactic and a common source. The tactic is non-violent resistance, or non-violent direct action, defined by Dr King in his most famous speech in the following terms:

- We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

As for the source, this could perhaps be best summarised in these words from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, written by William Blake in a time of great political and spiritual turmoil, between the American and the French Revolutions:

- I saw no God, nor heard any, in a finite organical perception; but my senses discover'd the infinite in every thing, and as I was then perswaded, & remain confirm'd; that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God, I cared not for consequences but wrote.

That’s it, in a nutshell. The voice of honest indignation.

Whenever a human being is roused to action by an abuse, whenever he or she feels compelled to make a stand, unable to bear the indignity of an injustice, wherever there is love and solidarity between human beings oppressed by wrongful laws, by inequality or discrimination, there you will find God.

Bhagavad Gita

The roots of the movement go back a long way: perhaps to the origins of religion itself.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Prince Arjuna is worrying about the great battle that is to take place the following day, in which many people will die. His charioteer is the god Krishna who, in the 700 verse poem following, answers all of his questions, exhorting Arjuna to stop hesitating and to do his duty, before revealing himself as the Supreme Deity.

Gandhi called the Bhagavad Gita his “spiritual dictionary” and took from it the concept of Karma Yoga, of spirituality through action. The idea is that we make our work a devotional act by offering it to the godhead. Gandhi saw his work as political engagement, and his devotional practice as his service to other human beings.

As he once said: “If you don't find God in the next person you meet, it is a waste of time looking for him further.”

Gandhi’s political engagement began in South Africa, where he went to practice after training at the bar in London. At the time (and indeed, until relatively recently) South Africa was divided by race laws which discriminated not only against the native population, but against the Indian minority too. This is the system known as apartheid, of separation by race. Gandhi, incensed by the injustices he encountered, became a prominent campaigner for Indian civil rights.

Henry David Thoreau

It was at this time that he discovered the writings of the almost unknown American writer, Henry David Thoreau: in particular an essay called “Civil Disobedience”.

Thoreau was a Transcendentalist. These were a group of New England Christians of the mid 19th Century who had broadened their reading matter to include the sacred texts of other religions. Specifically they had been reading classic Indian books, such as the Bhagavad Gita. They combined a healthy dose of American individualism with a dash of political idealism and an almost spiritual regard for the environment. They were American Romantics.

Thoreau was an abolitionist - that is he opposed the institution of slavery - and on this basis he refused to pay his taxes, for which he was thrown into Jail. It was only for one night but it was enough to give him the foundation for his famous essay, which was delivered as a lecture in January 1848, and published, under the title, Resistance to Civil Government, in 1849.

Put simply it is a call to disobey the law as a protest against government participation in unjust practices. As he says:

- “If the machine of government is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law.”

Martin Luther

Thoreau comes from a tradition of nonconformist Christianity which goes back to the origins of the protestant movement of late medieval Europe. The word “protestant” means “protester”. The protestants, originally, were radical dissenters against the authority of the Catholic Church. The first proponent was the German religious reformer Martin Luther, after whom Martin Luther King was named. Later the movement turned to full-scale revolution as the whole of Europe was torn apart, as more and more people threw off the yoke of a centralised Christianity and searched within themselves for a simpler and more authentic form of the religion. This was helped by the fact that the Bible had recently been translated from Latin into various native tongues, and had been widely promulgated by the invention of the printing press.

The gospels are a set of radical pacifist texts emphasising the importance of content over form, of poverty over wealth, of peace over war. Jesus hung around with the prostitutes and the tax-collectors and threw the money lenders from the Temple. He was the original political dissident. Reading the New Testament in your native language – as opposed to having it interpreted for you by a Church hierarchy – had a profound effect upon religious understanding throughout Europe.

It is out of this tradition that many nonconformist religious and political movements arose: from the Levellers of the English Civil War, to the Quakers, to the Jacobins, to Tom Paine, to William Blake, and beyond: to the revolutionary ideas of socialism and anarchism which came to the fore in the 19th century.

Vishnu

In the 20th century Gandhi brought a new, Eastern dimension to this movement. He was from a different tradition altogether. Born of a Vaishnavite merchant family, followers of Lord Vishnu, one of the figures in the Hindu Trinity, Gandhi summarised his religion in the following way:

- Hinduism tells everyone to worship God according to his own Faith or Dharma and so it lives at peace with all the religions.

In other words he grew up in an atmosphere of religious tolerance, and was himself, at an early age, influenced by the Jain monks who lived in his native Gujarat, with their philosophy of non-violence.

After his return to India from South Africa he became one of the central figures in the movement for Home Rule, leading a series of campaigns in the years running up to Independence. He is considered by many to be the father of the Indian nation, for which reason he is often called Bapu, which means father.

But Gandhi’s politics didn’t exist in isolation. A strict vegetarian throughout his life, an ascetic who used to go on long fasts, a celibate in his later years, who practised meditation and who lived in an ashram, Gandhi brought together his political and his spiritual life in a way that made it impossible to differentiate between the two. This is illustrated by his adoption of the dhoti as his mode of dress. As a British-trained barrister he had worn a suit and a tie. Putting on the dhoti was symbolic of a return to simplicity, as an act of solidarity with the Indian peasant, and as a protest against Western materialism, all at the same time. It was also, not coincidentally, the form of dress worn by the Indian sadhus, or Holy Men. To see Gandhi in his dhoti, with his shawl over his shoulder, in the presence of the British Prime Minister, and other world leaders, in their Western clothes, is to see him immediately as different, as coming from another place: not only geographically, but spiritually too.

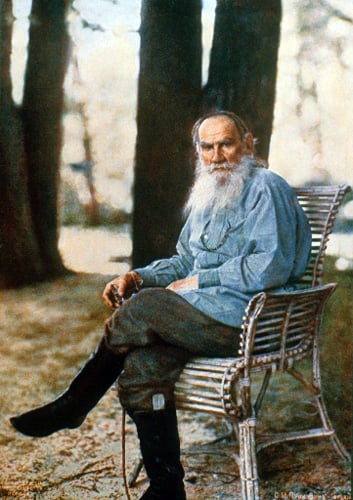

Tolstoy

Another of Gandhi’s influences was the world-renowned Russian novelist, Leo Tolstoy.

Born of an aristocratic background, in his later years Tolstoy renounced his privilege and became a political and moral thinker of great stature. He based his philosophy upon a combination of the Sermon on the Mount, and the anarchist writings of Proudon and Kropotkin, for which reason he is known as a Christian anarchist. He was deeply influenced by Jesus’ injunction to turn the other cheek and was a pacifist. It is his pacifism which separates him from the other anarchists, who were drawn to the idea of violent revolution.

In 1908 Tolstoy wrote an essay called A Letter to a Hindu. The letter contains instructions on how the Indian people might throw off British colonial rule by using passive resistance. Gandhi read the essay and began corresponding with the great man. The two of them continued to exchange letters throughout the final year of Tolstoy’s life, from 1909 to 1910.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece of political writing was The Kingdom of God is Within You. It came out in 1894 in Germany, having been banned in his native Russia. It is a book that Gandhi revered, and whose ideas he continued to follow throughout his life.

It was in imitation of Tolstoy that Gandhi adopted peasant dress. The two men shared other traits too. Both lived communally. Both were vegetarians and became celibate in later life. Both gave up their wealth, preferring a life of poverty and simplicity. Both adopted non-violent resistance to counter the violence of the State.

Tolstoy’s political views can be summarised in the following words, written in a letter to his friend Vasily Botkin in 1857:

- “The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.”

Martin Luther King

Another person who drew on Tolstoy’s political work, as well as on the work of Gandhi, was Dr. Martin Luther King jr. The son of a Baptist preacher, and a preacher himself, it was Dr King who became the de facto leader of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, from the mid fifties till his death in 1968.

You will know his most famous speech, of course. It is a speech which changed history.

It was delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC on August the 28th 1963 on the occasion of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom which had been called, in part, to demonstrate support for the civil rights legislation proposed by President Kennedy in June that year.

It is a speech which summed up in its short span the aspirations of a generation, which articulated the mood not only of his nation, but of a world stirring in its hunger for justice, in its thirst for freedom. It is the repeated refrain, “I have a dream”, which makes it stand out, culminating in its most famous line:

- “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

And this is the summation of the speech, at once deeply personal and general, individual and universal, about his own life, his own children, his own dreams and aspirations, but spoken to us in a way that everyone can identify with, linking us together, drawing us in, embracing us, ensuring that no one will be left out.

Prophet

More than anything, watching the speech, we are impressed by Dr King’s presence. It’s like he has taken on the stature of a Prophet. The tone of his voice, the way he holds himself, the dignity of his bearing, seems born out of spirit. When he speaks he appears to animate the world around him. His eyes look out on this world from a place beyond this world. He judges the world not by the world’s standards, but by the standards of eternity.

I would love to be able to add at this point that no one could possibly disagree with him, except, of course, that this isn’t true. The architects of racial segregation continued to oppose Dr King throughout his life. Agent William C Sullivan, of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, for example, wrote a memo about him the day after the speech which stated:

- We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation.

By the time of his death, five years later – blasted by a sniper’s bullet on the balcony of his hotel in Memphis, Tennessee - he had expanded the area of his concerns, by coming out strongly against the Vietnam War, by supporting striking sanitation workers, and by attacking world poverty. He had recognised poverty as a form of segregation, for whites as well as for blacks. He was no longer only talking about civil rights: he was emphasising the interrelatedness of all people, and taking on issues which were of concern to human beings throughout the world.

The day before his death he had delivered a speech to a small crowd in which he foretold his own end.

- Well, I don't know what will happen now; we've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life - longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over, and I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the Promised Land. And so I'm happy tonight; I'm not worried about anything; I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

Those were the last words he ever spoke in public.

Contradiction

But maybe there is a contradiction here. Generally speaking involvement in politics means engagement in the affairs of the world, while many spiritual traditions demand separation. Often spiritual people keep their distance from politics for fear of being tainted by it. Politics implies compromise. It is confusing, messy, full of contradictions and dirty dealings and is often an unpleasant reminder of the almost infinite human susceptibility to corruption. Perhaps, as a spiritual person, I could do without this.

The form of spirituality we have been discussing here, Engaged Spirituality, takes the opposite view.

It says that my engagement with the world can inform my spiritual practice, while my spiritual practice will help in my understanding of the world. If the political world is corrupt it is only because people have allowed it to corrupt them. Or perhaps politics attracts a certain kind of person, one who is already corrupt. Engaged Spirituality, on the other hand, brings a person’s spiritual practice into their political life, thus making them less inclined to take the bribe or to undervalue another person’s humanity. Why leave politics to the political? Why not infuse the political world with our spiritual values? And if we find ourselves unable to resist the lure of corruption, maybe this shows that our spirituality was fake in the first place, which at least means we have learned a lesson about ourselves.

Like Gandhi’s dhoti, more than one meaning can be expressed by the same act.

Thich Nhat Hanh

The term “Engaged Spirituality” comes from the Engaged Buddhism of Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk and peace activist who protested against the Vietnam War and who influenced Martin Luther King in his views.

Thich Nhat Hanh was influenced by Gandhi who was influenced by Leo Tolstoy who was influenced by Thoreau who was influenced by the Bhagavad Gita. This shows how ancient the movement is, and how Ecumenical. I would argue it even extends to people who would not consider themselves spiritual in any way.

A selfless act is a devotional act whether the person committing it believes in God or not.

When the Industrial Workers of the World attempted to organise American workers into one big union in the early part of the last century, recruiting women and blacks into the ranks of their leadership – challenging racism, sexism and capitalism at the same time – while standing up to the brute force of the American State, it was a spiritual act, one that both Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi would have recognised. And despite that fact that we have traced the movement to its origins in the protestant reformation, it also includes the practitioners of Liberation Theology, the form of politically engaged Catholicism which swept Latin America in the last decades of the last century, and which clearly influences the current Pope. If you want to read a story of real love and sacrifice, then look up the name of Archbishop Oscar Romero.

We could go on. The story is never ending. It is the story of the eternal battle between good and evil carried out in the political world. Wherever there is injustice, just men and women will rise up against it. Wherever there is corruption, people will take a stand. What all the people in this story have in common is love.

And that is the essence of Satyagraha. It is the power of love made manifest in the world. It is not tied to any particular religion, or to any particular philosophy. Some religious people have it, some don’t. Some people who are not religious have it. You can tell by their bearing, by the tone of their voice, and the sacrifices they are willing to make.

Brian Haw

However, we will end with the story of Brian Haw, who some will recognise as Britain’s own Mahatma Gandhi, our own Martin Luther King.

I wrote a short article about him recently which I put up on the internet. I was very surprised to discover how many people hadn’t heard of him.

Brian was an Evangelical Christian who, moved by the plight of children suffering under the sanctions in Iraq, set up a protest camp in Parliament Square. He was there from early in 2001 almost till his death in 2011. Later, following 9/11, his protest evolved into a critique of British and American wars in the Middle East. But though Brian was very clear about his own religion, he was also very inclusive in his attitude to other people’s religions.

He was defending the rights of Muslim children to have a life. Whenever he appeared on Al Jazeera or other Middle Eastern TV channels (more often than he ever appeared on British TV) he would greet his audience with the words “Salaam Alaikum”, meaning “peace be with you” in Arabic.

He made it clear that his God was the same as their God.

What made him so fundamental to our understanding at the time was that the people he was opposed to – Tony Blair and George W Bush – also claimed to be Christians. What Brian did was to expose them. If he was a Christian, then they could not be. It’s as simple as that.

Bapu

Brian’s profound spiritual insight came with his recognition of all children as his own children. One of his famous placards put it this way: Stop Killing Our Kids, it said. Our kids, not just their kids. Everyone’s kids. He left his own children, his own home, his own family, and went to live on the street in order to emphasise this. He adopted the human family as his own. By this act, this realisation, he threw off the shackles of his tribal identity and embraced the whole world.

He too became a Bapu, a father to the world.

His great strength was his indomitable spirit – his sheer bloody mindedness, you might say - which refused to allow him to give up. He was often beaten up late at night. He was picked upon by police officers, by members of the armed forces and by drunks. He had his tent and his sleeping bag confiscated. Nevertheless he stayed put, night and day, week in week out, year after year, homeless and destitute in a spiritual place. Like Martin Luther King at the Lincoln Memorial, he transformed Parliament Square by his presence, turning it into a living Temple.

Laws were passed in an attempt to remove him. They failed.

He was a man who scorned material possession in favour of spiritual truth. He was like an Indian ascetic, living a life of poverty, living off alms.

And I defy anyone watching him not to see the love flaming from his eyes, not to feel his soul-energy even at this distance, not to recognise him as a living embodiment of Satyagraha in our modern world.

He died in 2011 of lung cancer, probably brought on brought on by constant exposure to pollution in that traffic-ridden spot in the middle of London.

He was an honourable heir to the tradition. He won’t be the last.

Is it right to break the law when confronted by injustice?

© 2014 Christopher James Stone